Meet the oldest survivor of the Kindertransport.

86 years ago today, Gabriele Weiss arrived in England, a terrified 12-year-old child fleeing the Nazis...

It is my privilege to share her remarkable story with you today…

It’s midnight. The dark and smoky Viennese train station is festooned with swastika flags and crawling with jackbooted Nazis. Twelve-year-old Gabriele grips onto her beloved grandmother’s hand trying to be brave, but inside she is terrified. Train doors start to slam and a whistle sounds.

‘Now my darling, you must promise to write,’ says her grandmother as she ushers her onboard.

Gabriele longs to cling to the safety of her grandmother’s arms. Instead she grips her teddy bear and holding one tiny suitcase – all she has in the world - boards the train feeling like her little heart might explode.

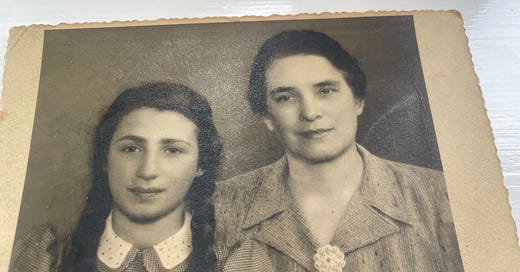

Gabriele and her grandmother, also called Gabriele, taken shortly before she fled.

As the train pulls out of the station and her grandmother’s face fades into the clouds of smoke, Gabriele knows that this is it – she is all alone on a train bound for a country where she knows no one. One thought drums repeatedly through her mind. Will she ever see her beloved grandmother again?

In April 1939, Gabriele Weiss was brought to the England as a child refugee fleeing Nazi persecution on a scheme known as the Kindertransport. From December 1938 until May 1940, the Kindertransport efforts brought 10,000 predominately Jewish children to safety in Great Britain.

Many of these children hadn’t just lost their homes, but also countless family members who had been deported to ghettos and concentration camps. England offered up a safe haven.

Now a great-grandmother herself, and living in the north of England, 98-year-old Gabriele still has a vivid memory of the chaos and fear as the Nazis took control..

‘My mother Hildegard had died when I was eight and my father Josef had to work, so I was sent a convent school in the week, returning home to Vienna at weekends where I stayed with my grandmother, who I was named after. She and I were very close. In March 1938 we watched the Nazis march into Vienna and immediately our lives changed.’

Gabriele’s mother had been Christian, but her father was Jewish. She was labelled as a 'mischling' - a Nazi German term for a person of mixed blood and was forced to wear a yellow star.

‘The star pointed me out as different. I had things thrown at me and I was called names, like ‘Dirty little Jew’,’ Gabriele recalls.

But it wasn’t until the night of November 9 1938, Kristallnacht (the night of broken glass) that the young girl's life became endangered.

‘I remember listening to the sound of gun fire and smashing glass as Nazi stormtroopers destroyed Jewish homes and businesses and attacked innocent civilians,' she recalls.

‘The weekend after Kristallnacht my father disappeared and I never saw him again.’

Gabriele believes he went into hiding, only to be found and deported to a camp later in the war.

Realising the extreme danger her Jewish granddaughter was in, Gabriele’s grandmother approached the Catholic Committee for Refugees and paid a £50 bond (around £3,000 today) to secure her granddaughter a place on the Kindertransport. Even after eighty-five years that fateful journey is indelibly seared into Gabriele’s mind.

‘After the train left Vienna the Gestapo got on at each stop. Each child wore a label showing their name and number and the Nazi officials constantly checked these against their lists. I later found out that my grandmother showed little emotion as she had been ordered by the Nazi officials that there must be no emotional outbursts.’

Bewildered, Gabriele sat silently on the train as it chugged its way to the Hook of Holland. All around her children aged between three and 17, cried for their parents. Gabriele was frozen in shock and fear and spoke to no-one, staring out at the unfolding countryside in a state of disbelief.

After crossing the North Sea by boat, the children arrived in Harwich and were met by committees from Jewish, Catholic, Protestant and Quaker organisations.

Tired and overwhelmed, Gabriele felt relieved when a tall, elegant lady stepped out of the crowd and made a beeline for her.

‘A woman from the Catholic Committee for Refugees called Miss Bagot met me. She had a kind face and I felt safe with her. She put me on a train from Waterloo to Aldershot. I spoke no English and so she had written the name of the station on a piece of paper. I spent the whole journey anxiously checking I hadn’t missed my stop.’

In Aldershot, a garrison town in Hampshire, Gabriele’s journey came to an end. ‘I was met by my foster parents who took me to their home.’

In her new bedroom Gabriele unpacked her clothes and precious travelling companion, Teddy and to her relief, found her grandmother had the foresight to hide forbidden writing materials at the bottom of her case.

Gabriele was enrolled at a local school and to begin with ,life was good. Her fellow school mates helped her to learn English and she wrote to her grandmother every week.

As soon as war was declared her grandmother’s letters abruptly stopped and Gabriele’s mind swirled with fears as to both her and her father’s fate, living under Nazi occupation. But she has also had problems closer to home.

‘After my foster father left, my foster mother treated me differently, forcing me to do lots of housework. I must have confided my upset to someone as two months later, the headmistress called me in and there in her office was Miss Bagot.’ Her saviour had come to her rescue once again.

Miss Bagot took Gabriele to a Catholic boarding school in Ashford in Kent.

‘I became a permanent resident as I had no official home, staying with the nuns during school holidays. They were kind and exceptional teachers and thanks to them I passed all my exams.’

The kindness of the nuns and being able to speak the language eased Gabriele’s home sickness as she began to put down roots in her new adopted country. But despite this there was an acute sense of time passing, milestones going unmarked, birthdays missed. By the time she began training to be a nursery nurse she was 16 years old, fluent in English and blossoming into a beautiful young woman. Would her father and grandmother – if still alive – even recognise her?

Gabriele after completing her training.

From there, Gabriele moved to a convent in Mill Hill, London where she began her training. In between learning to change nappies and bathe babies, she spent sleepless nights in air raid shelters as Nazi bombs rained down on the capital.

‘One morning we came out of the shelter and was astonished to see that the sky over London was completely red. It seemed as if the whole of London was burning.’

Despite the cataclysmic turn of events, Gabriele passed her Nursery Nursing Diploma and found a job with a kind and loving family in Surrey. Only one thing marred her new found happiness, the wall of silence from her grandmother. Gabriele knew that people living in Nazi occupied countries were not permitted to write to Allied countries so could only imagine what had become of the woman she adored.

‘After the war broke out my grandmother’s regular letters abruptly stopped. She was never very far from my thoughts.’

On V.E day in May 1945, Gabriele travelled to London with her fellow nannies. ‘We went to Buckingham Palace and joined the crowds. A tremendous cheer went up when the King and Queen, joined by Princess Elizabeth and Margaret came out onto the balcony. There was an outpouring of pure joy.’

But on the train home, the bubble burst as fears over her grandmother began to sink in. She wrote a letter but it was returned, stamped ‘not known at this address.’ Gabriele travelled back to London and consulted the Red Cross.

‘Despite searching, nothing turned up for my father and it was concluded that he must have died in a concentration camp.’

Gabriele’s fragile hope was shattered as the ramifications of losing her only surviving parent sank in. Only one shaft of light pierced the darkness. ‘Out of the blue I received a letter from my grandmother! She had survived the war and was still living in Vienna. The relief was indescribable that my beloved Gross mama (grandmother) had survived. Meeting up however was difficult as neither of us had the means to travel.’

Instead, Gabriele threw herself into a life in post-war Britain. In 1946 she swore allegiance to the King and became a proud British citizen, a joy only surpassed by being accepted for teacher training at a college in Country Durham. It was here that she met tall, movie star handsome RAF flight sergeant Ken Keenaghan. Romance blossomed and in 1948 Ken proposed, spending his demob money on a car and an engagement ring.

There was one person Gabriele most wanted to share her news with – her grandmother. Thoughtful Ken set about plotting their reunion.

‘In the summer of 1951, as a surprise, Ken made plans to take the car and drive us to Vienna so I could be reunited with my grandmother. It was a stressful journey as we had to travel through so many different zones and submit papers for examination. Austria was divided into four different zones, jointly occupied by the United States, Great Britain, Russia and France. Vienna was similarly sub-divided. It was a complicated and exhausting journey.’

All the frustration melted away however when she knocked on her grandmother’s door. Her grandmother’s previous home had been requisitioned by the Germans and she had been forced to move into a much smaller apartment in Vienna. She had been reduced in all ways possible by the war. The door swung open and Gabriele felt the breath leave her body. Her grandmother was older, frailer, greyer, but there was no mistaking the love and kindness that shone from the face that Gabriele had dreamt of for so long. The pair stumbled into each other’s arms and clung to one another, speechless with emotion.

‘The last time I’d seen her had been 13 years previously on the train platform in Vienna. There was a mixture of complete joy and sadness. Joy that she was alive, but sadness at her appearance. She was worn down by her cares and living frugally in a tiny apartment. Her beautiful home had been stolen from her by the Nazis. But she was alive. We were both survivors and the realisation was enormously emotional. We clung to each other as Ken, smiling, looked on.’

Now, 74 years on from the emotional reunion, Gabriele, fully understands the sacrifices her remarkable grandmother made.

‘To be able to put your grandchild on a train and send her off into the unknown takes enormous courage, I don’t know if I would have been able to do the same,’ Gabriele reflects.

The pair were determined to stay in touch after so many years forced apart. In July 1955 it was her grandmother’s turn to travel and she arrived in England to meet her first grandchild when Gabriele gave birth to her daughter Pat, followed by Christine in March 1958. As the girls grew up Gabriele took them to visit their great grandmother in Vienna each year.

‘She was so delighted to be around her great-grandchildren. My girls called her Grandma Noddy, because, not speaking English, she’d just sit there and smile and nod.’

Her beloved grandmother died suddenly in November 1974, four months shy of her 90th birthday. ‘It happened so quickly I did not get a chance to say goodbye,’ Gabriele says, ‘but fortunately we had all been to see her three months previously during the summer holidays.

‘I grieved for the loss of a dear and courageous lady. She had sacrificed so much for my freedom. She lost everything in the war but she never complained, not once.’

Gabriele went on to become a headteacher in the North East and in 2019 was awarded the British Empire Medal for services to Holocaust education.

‘After I retired I was asked to deliver a talk at a school about my experiences, but word spread and soon I was invited to many schools and other establishments of education. For my very first talk I wrote a poem to help illustrate the emotion I felt about my departure and the long Kindertransport journey.’

‘My wonderful husband Ken died shortly before the birth of his first grandchild in 1991. I miss him every day but I never forget what he did for me, or fail to appreciate the happy life we forged together.’

Gabriele is equally grateful when she reflects on the kindness of so many people who helped her to build her new life in Britain. ‘I was unlucky in childhood, but I’ve been extremely lucky since and I can only be grateful for all the wonderful people involved in the Kindertransport scheme which saved my life.

But when it comes to the state of the world today, Gabriele despairs. ‘The whole world is in such a mess, so angry and full of hate, I sometimes feel as if we haven’t learnt a thing. Since the Holocaust there have been other genocides. Why don’t we learn? On the whole I still believe in the goodness of people.’

‘Today, aged 98, I reflect on a rich and full life. It’s so important that the next generation know the unflinching truth of the Holocaust. It must never be allowed to happen again. I do talks in schools and I take along my teddy bear who accompanied me on the train from Vienna. I still have him; he’s a bit threadbare these days but he’s a precious reminder of the past we should never forget.’

Gabriele’s poem: The Departure.

Children were named and numbered,

Their faces showed great fears.

The station platform was crowded,

People shed bitter tears.

The suitcase was heavy, the journey ahead would be long.

We were just little children and not very strong.

A suitcase and soft toy was all we could take,

Came the midnight departure and the last loving embrace.

To listen to my interview with Gabriele on my podcast, click here.

Unimaginable decision for her brave grandmother to make on her behalf. Not yet a century ago, that history resides in our cultural consciousness. May we always remember their sacrifices in hopes they will never be necessary again!

Thank you so much for telling this story. It is sad and uplifting and should be educational. Again, thank you both.