The Titanic's final secrets

In April 1912, the so-called 'Ship of Dreams' hit an iceberg and sunk. Why, 113 years on, does the Titanic still hold us in its thrall?

Screams. The pounding of feet. An ominous creaking. Four-year-old Louise Kink can’t make sense of what is happening. Her mother, also called Louise, and father Alfred have shaken her awake in the dead of night, hastily put on her boots and swept a blanket around her. Up on deck, it is icy cold. She feels her mother’s arms tightly wrapped around her as they are lowered down into a lifeboat.

‘Papa,’ she calls. He is being held back by a crowd of seamen who have formed a protective chain around the lifeboat. At the last minute, he breaks through the human chain and leaps aboard. They are then rowed away on Lifeboat Number 2, and can only watch, mute with horror, as 30 minutes later, at 2.20am, the mighty hulk of RMS Titanic slips beneath the black waters.

Eighty years later, when Louise, aged 84, dies in her bed in Wisconsin, her daughter Joan Randall finds a dusty box in the loft. An old pair of boots. A moth-eaten blanket. It is all that remains of the terrifying ordeal her mother survived but rarely spoke of.

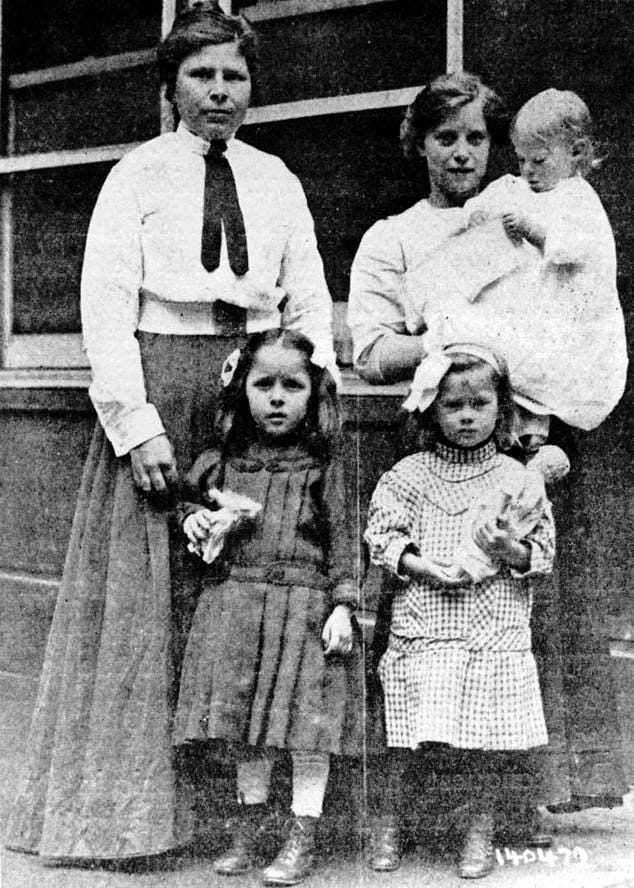

Louise Kink (front left, her mother behind) in the boots she wore as she escaped the Titanic.

Today, you can see those shoes at Titanic: The Exhibition, one of 200 exhibits on display, alongside full-size re-creations of rooms in the ship, built to give visitors a more immersive experience. It is a tantalisingly tangible link to the past.

What is it about the sinking of the ‘unsinkable ship’ that has had such an iron grip on our imaginations and elevates a battered old pair of children’s shoes to something now worth in the region of £10,000? One hundred and thirteen years on from when the 46,328-ton ship, HMS Titanic collided with an iceberg on April 14th, 1912, the doomed vessel has spawned myths and legends, to say nothing of a thriving economy. In 2012 alone, three hundred books on Titanic were published in one year and James Cameron’s 1997 film Titanic, became a blockbuster.

Titanic: The Exhibition, touring the world, currently in Seattle, features recreated rooms to allow visitors an immersive experience. Using two hundred new exhibits, like Louise’s shoes, it provides a unique narrative experience, telling countless stories about the fates and heroic deeds on board.

But in our quest to get closer to the so-called ‘Ships of Dreams’, are we at risk of overlooking the deep human tragedy at the root of this? There were 2208 people on board (1309 passengers and 899 crew) Out of that total, 1496 passengers and crew members perished, fifty-one of them children (fifty of them from third class, one from first class) Are we are in danger of turning a disaster into a Disney experience?

Titanic historian, Claes-Göran Wetterholm from Stockholm, who was responsible for curating the new exhibition, believes not.

‘It is important to look again at the tragedy and dispel some commonly held myths,’ he insists.

‘The largest language was English as the largest passenger group was British. The second largest group was American. The third largest, was Swedish and then Irish, but did you know, the fifth largest passenger groups on the Titanic were Arabs? They came from Syria and Lebanon in search of new lives. They came by boat over the Mediterranean to join the Titanic at Cherbourg. There were also Spanish, German, Finnish and Norwegians on board.’

The narrative of women and children only in the lifeboats, doesn’t always bear resemblance to the truth, according to Claes-Göran. ‘The story goes that those who survived were women and children,’ he continues. ‘It’s not true. Three hundred and twenty three men survived, eighty per cent of them boarded lifeboats from the starboard side. They survived because Scottish First Officer William Murdoch, who was responsible for the evacuation on that side, didn’t prevent them from getting in.

‘On the portside, Second Officer, Englishman Charles Lightoller had a rule of women and children first and he took it literally. One lifeboat that could take sixty-five people, rowed away with twenty-eight, leaving men behind. Over on the starboard side, it was a different story. The last two boats to leave, boats 13 and 15, the majority were men.’

Another perception the exhibition shatters, is that third class accommodation was grim and airless.

‘Actually the accommodation in third class was considered good,’ says Claes-Göran. ‘It was all freshly painted, new and clean, the food was excellent and they were allowed alcohol. They even had flushing toilets, unheard of for 1912. The stewardesses in third class had to teach people how to use them.’

Claes-Göran’s interest in the doomed vessel began when he was a child. In the 1970s, he began studying Titanic by interviewing survivors and their relatives and delving deep into archives around the world. He has interviewed eleven survivors, but was most struck by the testimony of Eva Hart, who was seven at the time.

‘Eva told me of the screams she heard in the boat, but it became worse when they heard no more and her mother said that “now all had died’.’

Sadly there are no more opportunities to capture these stories. The last survivor of the Titanic was Millvina Dean from Hampshire, who died in 2009 aged 97. She was just a nine-week-old baby when she was lowered into a lifeboat, in a canvas mail bag. Her 32-year-old mother Ettie and 23-month-old brother Bertram survived, but her father also called Bertram, did not.

Millvina Dean

I interviewed Millvina shortly after the film Titanic was released and found a humble woman, genuinely astounded by the interest in her life. ‘I refuse to see the film,’ she told me, despite being invited to the red carpet premiere. ‘It would have made me think, did he jump overboard or did he go down with the ship? I would have been very emotional.’

When I visited her in the street named after her, she turned to me and asked. ‘Why do people look at me as a sort of celebrity?’

Claes-Göran believes this fascination, lies not in the sinking, but in our own identities and the ship is merely a metaphor for a bigger story on how we see ourselves.

‘We identify with the people on the ship. It could have been me or you and we ask ourselves. “Where would I have been, sipping champagne in first class, or bunking down below decks in third class? Would I have died or survived?”’ The sinking of the ship stripped back class. The incredibly rich, down to the ordinary immigrant, died in the same brutal way.’

But not, perhaps, on the same scale.

‘True,’ Claes-Göran admits. ‘Statistically, people from third class are only to be found in the last four large lifeboats, plus two collapsible lifeboats that were launched in the end. Apart from that you don’t find any third class. They weren’t locked in as portrayed in the film, but they did not find a way out and to start with no one told them how to get up on deck. They were left to drown.

‘I met the son of John Edward Hart, who was a third-class steward. Hart took groups of third-class passengers and guided them up on deck. He managed to bring approximately fifty passengers up, then he was ordered into lifeboat 15, by First Officer Murdoch. When that boat was rowed away there were hundreds of people still left below decks in third-class. His son, also called John, told me his father was haunted by that knowledge for the rest of his life before he died in 1954 in Paignton, Devon.’

Every single object in the exhibition has a story, like the gold wedding ring which belonged to Swedish third-class passenger, 30-year-old Elin Gerda Lindell. Elin and her 36-year-old husband Edvard Lindell, a young married couple planning new lives in Connecticut, had struggled up the sloping deck of the sinking ship, until it was too steep and, clasping hands, they slid back down into the icy waters, close to Collapsible A.

Edvard managed to get on board the lifeboat. He reached for his wife’s hand as she floated in the water, which was a perishing minus half-a-degree. (It’s estimated that ninety per cent of the passengers who died, didn’t drown, but froze to death)

‘He tried to pull his wife up into the lifeboat without capsizing the whole thing, but tragically, he dropped her and she disappeared under the water immediately,’ says Claes-Göran. ‘It was so incredibly cold and her fingers so frozen that her wedding ring slipped off her finger and dropped into the boat.’

The lifeboat was recovered one month later, with three decomposing corpses on board and the ring was discovered. Elin’s husband died of pneumonia and joined her in the watery depths. The ring was returned to Elin’s grief-stricken parents in Stockholm, via White Star Line and the Swedish Consulate. In the mid-eighties, Claes-Göran tracked down the Elin’s surviving family and persuaded them to allow him to display the ring and tell its tragic story.

Passengers Edvard and Elin Lindell. When the Titanic began to sink, they fell into the water, but while he managed to get into a lifeboat he couldn’t pull his wife in. She froze to death.

It’s the tiny personal objects salvaged from the Titanic that pack the biggest punch. A cigarette tin. A postcard. A third-class ticket that cost £8, the equivalent of a year’s wages for a working-class person. A ticket that would have been grafted for with dreams of a new life in America, but which tragically in so many cases ended before it had even begun.

‘There is a saying that you die twice. Once when your heart stops beating – and then when someone says your name for the last time,’ says Wetterholm. ‘By telling the story of these people, we are keeping their memory alive.’

The real-life Jack and Rose

Believed to be the inspiration behind lovers Jack and Rose, played by Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet in the Oscar-winning film Titanic, Henry Morley, 39, and Kate Phillips, 19, began an affair when she worked for his confectionery firm in Worcester. Despite the age gap, they ran away together, boarding the Titanic under fake names with dreams of a new life in California. However, only Kate survived the sinking and when she arrived in New York she found she was pregnant with his child, conceived on the ill-fated voyage. For the rest of her life she treasured the pendant given to her on board by Henry.

You can listen to my podcast interview with Claes-Göran Wetterholm by clicking here

Fascinating. The individual stories are so poignant. I saw the exhibition here in London some years ago. Very thought provoking. It was learning about titanic and its passengers that sparked my interest in ancestry..

This information is truly astounding! Thank you!