Recently I had lunch in London with a group of historical fiction writers. It’s always a soul-restoring occasion to get together and talk about books, edits, research, ideas (and other more frivolous stuff) fuelled by good food and a glass of bubbles.

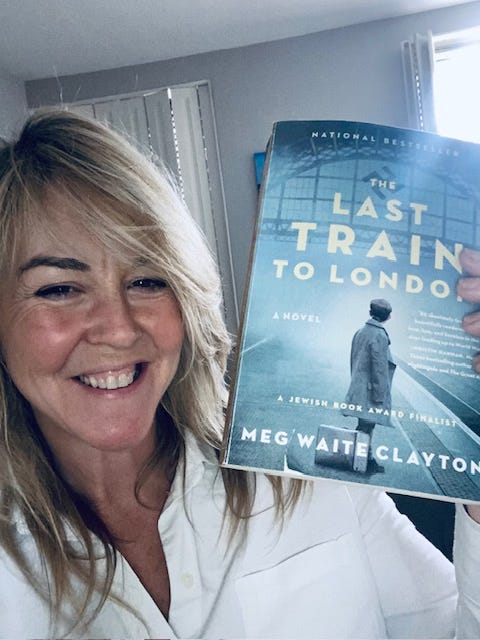

I had the pleasure of meeting author Meg Waite Clayton, visiting from the US, and was fascinated to hear about her novel, The Last Train to London based on the life of a woman I’d never heard about before. Truus Wijsmuller was a member of the Dutch resistance who risked her life to smuggle Jewish children out of Nazi Germany.

Child refugees from Germany and Austria at the Amsterdam Burgerweeshuis orphanage. Truus Wijsmuller stands at far left, looking at the children she helped save

Tante Truus, as she was known, was determined to save as many children as she could. After Britain passed a measure to take in at-risk child refugees from the German Reich, she dared to approach Adolf Eichmann, the man who would later help devise the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question,” You can read more about this exceptional woman in this Smithsonian piece. Meg was in London en route to the Netherlands to visit the sculpture of Truus. (A woman after my own heart, I once travelled over 300 miles to sniff a book, the only survivor of a Blitz fire)

Serendipity is a wonderful thing. Shortly after that lunch I was due to attend the 101st birthday party of a friend of mine. Like the children in Meg’s novel, Henry Glanz was rescued by the Kindertransport scheme and was one of the last children to board a train which brought him to safety in London.

I’d like to share two things with you, Henry’s story, and the chance to win Meg’s wonderful book, pictured here. Just by following you are automatically entered and I will pick a winner at random in one week.

From the Last Train to London, to the last boy to board the train to London.

Aged 15, Henry was one of the last children to board the Kindertransport train which helped to evacuate 10,000 Jewish children away from Adolf Hitler’s reign of terror in parts of Europe controlled by the Nazis.

Clutching one small leather suitcase, Henry waved goodbye to his mother and brother in Kiel, Germany and crossed the border into Holland just five hours before German forces invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. Henry’s younger sister Gisela, 11, had already been evacuated to England and his father Mordko had been forced to flee Kiel six months earlier after the Kristalnacht. His mother, Esther and 10-year-old brother Joachim were still trapped — he never saw them again. They were all murdered in Nazi concentration camps.

Henry’s gruelling journey took three days via a ferry which brought him and other bewildered children to Harwich. From there they were taken by train to London’s Liverpool Street, before ending up in North Wales. By the time he arrived at the freezing cold, run-down castle, Britain was at war.

Discovering his new home was an abandoned castle came as quite a shock.

Gwrych Castle acted as a safe haven for Jewish children fleeing the Nazi regime

‘It was midnight when we arrived and pitch black. There was no heating, lighting or toilets. Our beds were straw pallets and we had to wash in the Irish sea.’

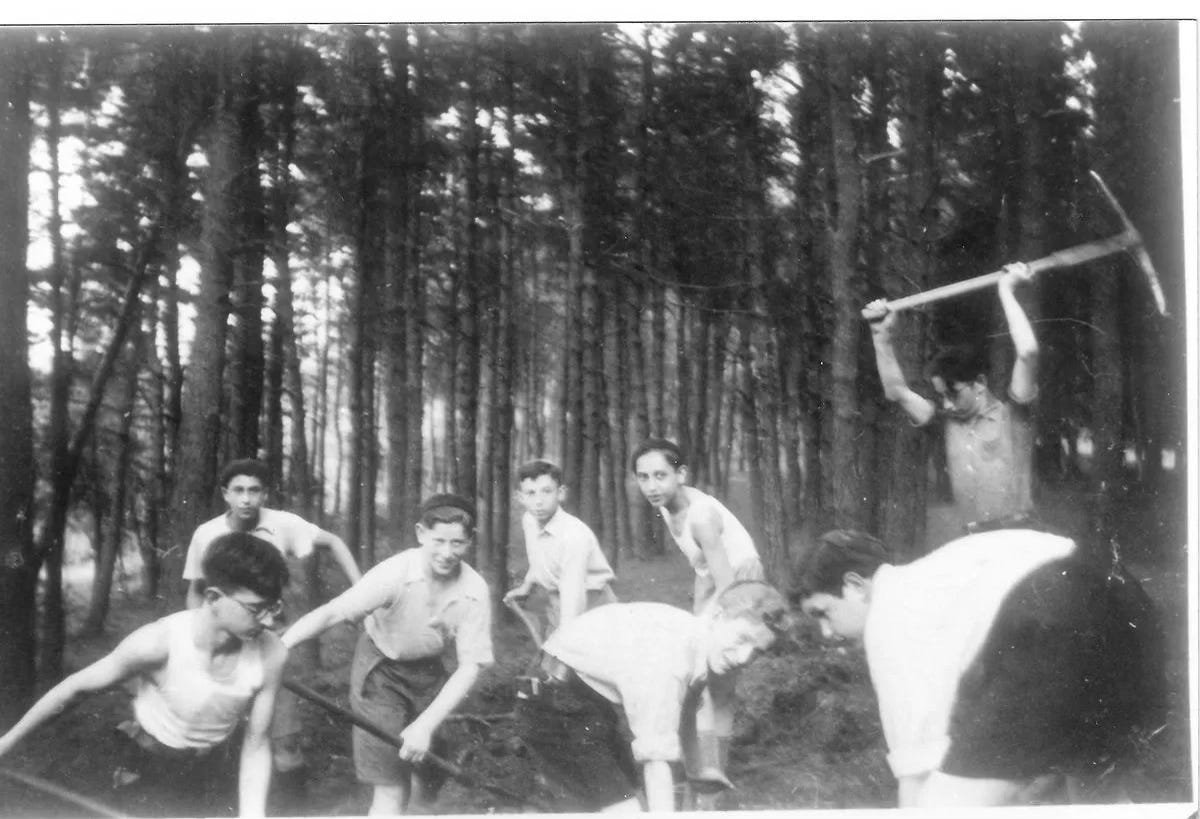

Henry was taught in a Hebrew school and got work helping out on local farms. Furniture was donated by a nearby Quaker community. In his spare time, he and the other youngsters roamed the four-story castle, complete with secret underground tunnels and surrounding woodland.

‘The children at the castle were split roughly evenly between boys and girls, I was the youngest,’ Henry recalls. ‘We were teenagers really and curious about life.

‘Us boys slept in dorms on the second floor of the castle, the girls slept on the third floor and the washing facilities were on the top. To try and look more mature than we were, we would cover our faces in shaving foam so that when we mixed with the girls in the wash facilities, they would think we were already shaving, but I only had bum fluff,’ Henry laughs. ‘But really I was very shy around the girls. I was sweet on a lovely blonde girl from Berlin called Hanni, but I never found the courage to talk to her, so I admired her from afar.’

According to Henry there were more rooms than they could ever explore and boys being boys they were drawn to the atmospheric network of underground tunnels.

‘Apparently, they were haunted, not that I ever knew, but even if I had I would never have believed it. We had run from the most frightening thing of all, the Nazi regime, so those tunnels held no fear for me.’

The boys were visited regularly by rabbis from London who would talk to them about politics and faith. They also played chess and football, and whilst at the castle, Henry learnt to speak French and Welsh, as well as fluent Hebrew.

‘I learnt that if I spoke in Welsh to the local farmers, I could get away with murder,’ he recalls.

The reception from the locals was a warm one.

‘Our nearest town was Abergele and I think us Jewish refugees became quite famous there. On one occasion, myself and three other boys were window-shopping in the town when a policeman approached us.

‘Two of my friends fled and the policeman chased after them. I was the only one who spoke fluent English so he asked me why they had run.

“If a policeman approaches Jewish children in Germany, it means trouble,” Henry told him.

“The policeman cried,” he recalls.

“He said: ‘Tell them that this is not Germany. Here a policeman is your friend. When you’re in trouble, you don’t run away from a policeman. You look for one.’

“A few days later several policemen came to the castle to talk to us about the British police - and they brought tea and cakes.”

A sense of safety wrapped itself around Henry for the first time in years.

Henry Glanz (4th from left) and the boys, all 15, working in the forest of Gwrych Castle

‘When the Blitz began in 1940, we could see the bombing of Liverpool from across the Irish sea, but we felt cocooned at the castle and away from danger. I fell in love with the beautiful Welsh countryside.

An idyllic adolescence, were it not for the unspeakable horrors unfolding on the continent. Never very far from his thoughts were the family he had been forced to leave behind.

‘I was homesick and missed them so very much. I wrote them letters via the Red Cross that cost two shillings. You had to say what you wanted in 25 words or less.’

Henry learnt that his father Mordko had been ordered to leave Germany and ended up in Belgium, while his mother and brother were interned in a deserted school in Leipzig.

‘The last sign of life I received from my mother and brother was a letter on the 21 October 1941 from Leipzig: “My dear beloved children, keep always together in love and faith, and G-d will bless you.”’

After 18 months, Henry and the other children had to leave when the castle owner, the 12th Earl of Dundonald, was forced to sell the estate for financial reasons.

While the others were sent to live and work on farms in the area, Henry, then 17, was determined to join his sister in London.

But with pocket money of just a shilling a week, he could only save enough money to get to Birmingham.

“They found me a hostel in Birmingham, where I stayed for three months, worked clearing bombed houses until I had saved enough money to go to London and find Gisela.

‘It was a very emotional reunion.’

The shocks did not end there. By the time war was in its fourth year, Henry was 19 and working in a factory in Acton, West London which made machine guns for the war effort. It was the middle of the night and Henry was on fire-watching duty during a raid.

‘The all-clear went when suddenly a young German airman just walked in through the door of the factory,’ says Henry. ‘He had parachuted out and landed near the factory, he was covered in blood and shaking like a leaf. The Irish lad I was firewatching with took one look at him and began to tremble.

“He’s got a gun.” We all froze and just stared at each other. Eventually I stepped forward. “Gib mir den Revolver", I said gently.

‘He handed it straight over and I stored it away out of reach. The Irish lad made him a cup of tea and gave him a cigarette and someone else ran to notify the authorities. Eventually, when this pilot calmed down, he turned to me. “How do you speak such good German?” he asked. “I grew up in Kiel, I am a Jewish refugee,” I replied.

‘The German pilot was stunned. “But you look just like him,” he replied, pointing to the Irish lad.

“What did you expect?” I said. “That I would have horns and a tail?”

The shocking incident revealed to Henry the true depth of Nazi brainwashing and its propaganda machine.

‘My colleague asked why I hadn’t shot the pilot and I told him that if I had, I would have been a barbarian like the Nazis,’ Henry reveals.

As soon as the war ended, Henry learned his mother and brother had died in Majdenek concentration camp in Poland in 1941.

It would be three years before he found out that his father had died in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

After the war, Henry served with the army in Munich as a postal censor, and it was here he met and started dating a young German woman.

‘She was a beautiful blonde woman and was curious about the Jewish faith. As a girl she had been part of the Hitler Youth girls movement and had been brainwashed about Jewish people,’ Henry recalls. ‘We were starting to get serious, but then one day I saw a photo of her as a child wearing her uniform with a Swastika on the arm. It chilled me to the bone and even though she was no longer in the party, I could never forget that photo.’

Henry left and returned to England where he met and fell in love with pretty East Ender Roberta, known as Bobby, who helped him to come to terms with the trauma of his childhood under the Nazis and the murder of his parents and brother.

‘I was 23 and she was 21. We were married in Croydon Synagogue, on her 23rd birthday in 1949. She gave me a new life.’

Together they had two sons and established that life together in East London.

Twenty years ago, Henry attended a reunion of the Kindertransport children and was thrilled to find many of his old friends from the castle there.

‘Hanni was there and we stayed in touch. Bobby and I visited her at her home in Fort Lauderdale and I plucked up the courage to tell her I was once sweet on her, she laughed and asked me why I had never told her. Her parents were murdered in the camps, as were most of the other Kindertransport children’s families.

‘Sadly, I don’t think too many of them can be alive anymore as I was the youngest.’

When Henry’s two sons Jeffrey and Mark were 10 and 6, he and Bobby took them to the castle.

‘They went wild when I showed them all the secret nooks and crannies. They loved it.’

Sadly Henry’s beloved Bobby died aged 90 in 2016, after 67 years of marriage.

‘We danced at the wedding when we met all those years ago and we never stopped dancing. Every day I feel grateful to her for all those happy years of marriage.’

Henry also feels a huge debt of gratitude to the country who offered him a safe haven during the war.

‘Israel is my biological mother and Britain is my adopted father.’

Henry is an amazing man - clever, kind, creative and curious about life. Every time we meet, whether that be socially distanced in the park with a flask of tea during Covid, or over smoked salmon and cream cheese beigels at Rinkiffs, I learn something new.

We danced together at his birthday. I hope he continues dancing, and sharing his remarkable story, for many more years to come.

Oh Kate! I always feel all of your stories! Thank you for sharing with us!❤️

I love all these stories you share so much! Thank you for sharing them with us❤️